like a powder keg trailing its incendiary guts all over the world

Iranians are no good at goodbyes

Hi friends,

This week I wanted to share something that was both extremely difficult to write and is deeply close to my heart. This is by no means a comprehensive account of the tragic events—and human rights crises—that have been unfolding in Iran, but it is a personal one.

Iranians have never been good at saying goodbye. We are taught to kiss both cheeks when greeting and parting with friends and family, to drink strong and scalding black tea multiple times throughout the day, that it is the height of discourtesy not to ensure guests are well-cared for, and that certain superstitions must be adhered to in order to avoid cheshm, or the evil eye. But goodbye?

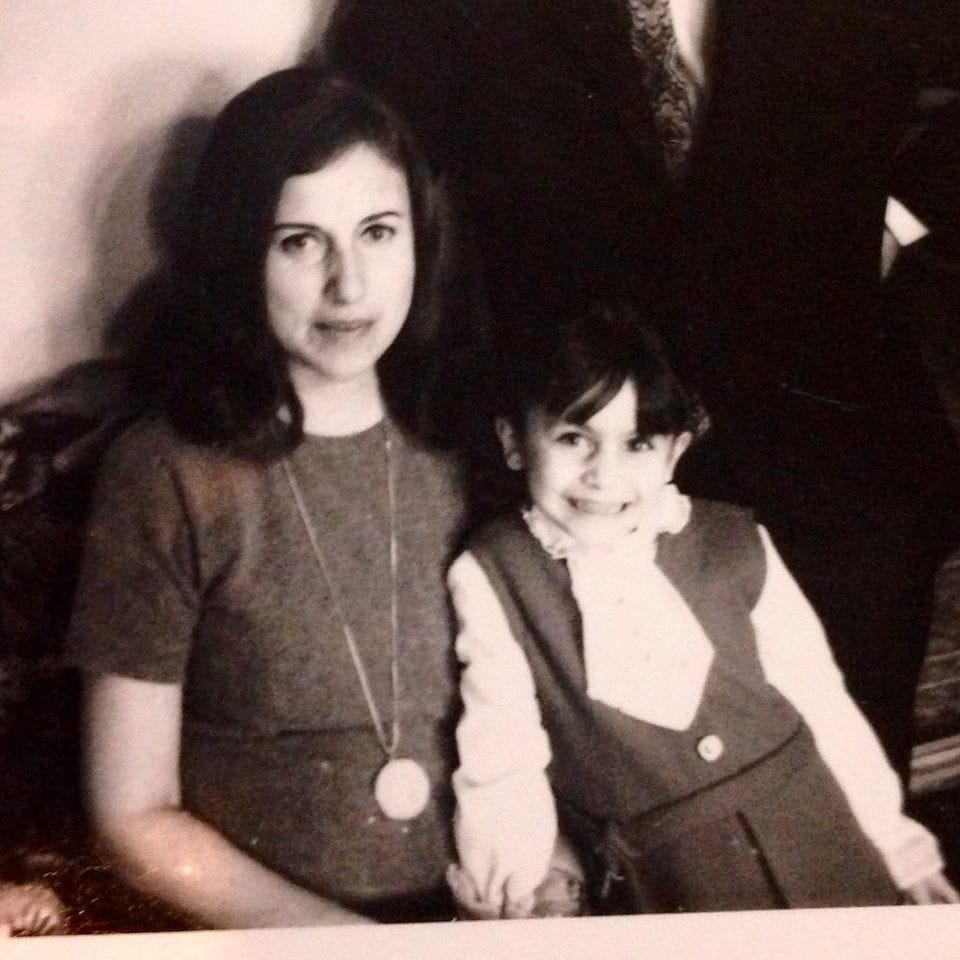

As a child I watched my parents exchange flurries of kisses with their friends, and perfunctorily did it myself. I drank the tea with a splash of milk and honey. Still do. Leaving a social gathering could take hours, and I was impatient. Still am. Patience didn’t come until well into my late twenties, and it doesn’t sit naturally.

I think often of the person I would have been if I was not a child of immigrants, if I was not born in this country. If my parents hadn’t, separately, both moved to the US, a place that was decidedly unkind to Iranians after the hostage crisis of the 1980s. My 15-year-old mother landed in New York with her sister and parents, and my father emigrated with his older brother to attend college in Pennsylvania.

Both of my parents made it to the States just before the Iranian Revolution changed everything. But in the summer of 1978, my mother, grandmother, grandfather, and aunt returned to Iran for my aunt’s July wedding. My mother told me of the whispers that started soon after they arrived—one person after another, asking if they’d heard of one particular gathering, or seen those flyers denouncing the Shah’s regime.

Remember, she told me, the Shah’s regime was still a dictatorship. No one could overtly speak against him or his secret police; but little by little, political flyers spread through cities (no phones to spread the news, of course), and people began to gather to speak openly about freedom of speech, about fighting for their political freedoms.

This was different, she said. Something was happening.

It was when a movie theater showing a political film in the city of Abadan was set afire that the fuse truly ignited. 600 people burned alive that night. All over, it was said that the Shah and his secret police were responsible for the tragedy.

Later, it was proven that another regime—one that was far more conservative, one that was ultra-religious, one that we know today—was to blame, though they certainly knew where to point their fingers to further goad the collective anger. So many protesters were killed by the police or the Shah’s army that the Friday my family left Iran became known as “Black Friday.”

People came into the streets and weren’t afraid of being shot, just like now, my mother said. The women resisted all along. This is what I remember.

The women in my family are strong-willed. We talk loud and laugh louder, and we’ve always had the spirit of rebellion in us. I was never taught to shy away from the expression of strong emotions—where my mother loves fiercely, so too does she grieve.

Today I wonder, in what ways would I have rebelled differently, had she never left her homeland? Would another version of me have pushed my hijab1 back to proudly display the smallest slice of hair atop my head, the way 22-year-old Mahsa Amini did? In what ways would I have staged my own revolt, like many young women in Iran before Mahsa and since—and in what ways would I have done otherwise: forced myself down, made myself smaller to fit myself along the corrosive edges of the dictates of men?

I don’t have to wonder about Mahsa; I know. We all know.

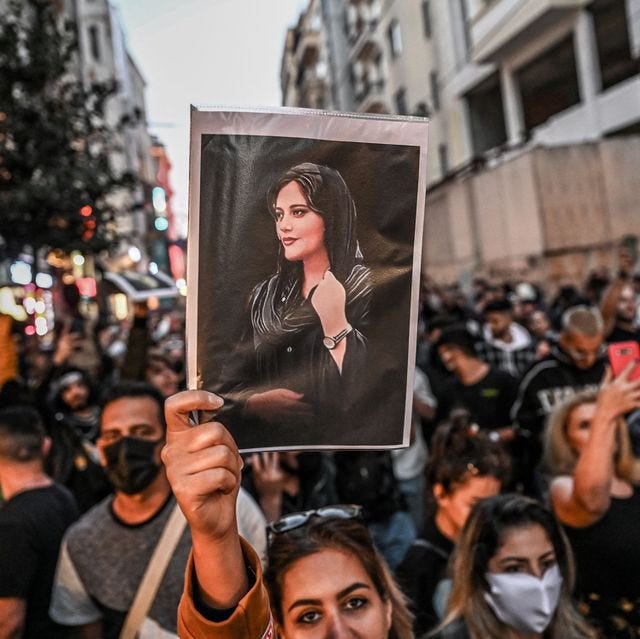

Improper hijab, they said of her “crime.” Read: a small flame of defiance, burning bright to help light others’ way along the path.

“Morality” police. Read: a war of men against women, of the violent enforcers of an oppressive regime, of a government that passes down mandatory veiling laws in order to police women’s clothing and bodies according to those cruel dictates of misogyny, patriarchy, and totalitarianism. Make no mistake—the Iranian people are protesting for the right to choose how they adorn their bodies.2 But the movement has also become about so much more than the forced dress code.

In a recent episode of New York Times’ The Daily, journalist Farnaz Fassihi reports that after Mahsa, who was traveling with her brother, left a metro station in Tehran, they were stopped by the morality police. Though from the photos her family later provided, anyone can see that she was clearly not in violation of the hijab law (she wore it along with a long, loose black robe), and though she and her brother resisted them, the encounter resulted in the police stealing Mahsa away in a van filled with other frightened women who knew exactly where they were being taken to.

After Mahsa was detained, at a center many Iranians know of as a place of nightmares, her brother followed her there. As he waited outside, he and the family members of other detainees could hear an argument break out; soon after that, an ambulance arrived to remove a young woman from the center and rush her to the hospital. Someone had collapsed inside the center. That someone was Mahsa.

And, after hovering in a coma due to traumatic head injuries, with blood trickling from her ears, she died mere days later.

Niloofar Hamedi, who was the first Iranian journalist to break the news of Mahsa’s death, has since been arrested, her Twitter account suspended3, and is now in solitary confinement. She beat the news like a drum she held before her. All around the world, we can still hear it reverberate like a heartbeat, a rallying cry echoing out over the streets. Like a powder keg trailing its incendiary guts everywhere it goes.

And now, thousands of Iranian women, men, and even children continue to rage against the injustice—remaining in those streets, protesting, dodging the militia’s rain of bullets. They publicly burn their hijabs, go without them, and cut their hair in gestures of open defiance in cities across the country. “Woman, life, freedom!” they cry. “Death to the dictator!” they chant.

They lead what could become a revolution as they resist the tyranny they have been forced to contend with for so many years.4 Rightfully so.

And their blood, like the blood of those who protested before them—in the years 2019, 2009, and 1979, among others—is spilled again and again.

I cannot speak for them; I cannot bring the words into being that so many of them will never now be able to speak. All I can think is what I’ve always thought: Iranians have never been good at goodbyes. Khodahafez.

And they never should have been forced to say it to Mahsa Amini.

Nazanin Boniadi, Dr. Nina Ansary, Christiane Amanpour, and Golshifteh Farahani are some incredible resources to start with if you’re interested in amplifying the voices of Iranian women and their activism, and learning more about the ongoing human rights crisis in Iran. Find more ways to provide support here.

xx

Kimia

I wasn’t taught to call it a “hijab” growing up. To this day, my mother calls it roosari or chador, the former of which translates, quite literally, to “on top of the head.” A chador is a veil that serves as a slight variation of the burka, which doesn’t fully cover the face the way a Saudi Arabian burka would. Only after the Iranian Revolution did the headscarf and covering start being referred to in Iran as “compulsory hijab”.

The point isn’t to force women to cover their heads and the curves of their bodies or not; there are many religious women who choose to don the hijab. It’s that all women should have the right to choose.

Internet access, as well as access to social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, has been blocked, with WhatsApp heavily filtered.

It has also brought together a global outpouring of solidarity, empathy, and rage against the Islamic Republic, as people protest with them in California, Paris, London, and all over the world.

How are there no comments on this powerful piece... ? I could barely choke back tears reading this. I've had friends in your community for many years Kimia. Extraordinary strength and resilience, and beauty, they carry.

I'm sure the people of Iran through their own efforts, will be free. The sacrifices and valor of those seeking change and those who have been trodden on are in my thoughts and prayers.